How to approach Employee Stock Ownership Plans (ESOPs)

Thanks to Jeff Erickson at Carta and Elyse Kent at Access for help on this post.

Introduction

In the mid 1900s, the idea of giving equity to compensate employees was effectively unheard of, yet today it is a standard practice for almost all publicly listed companies and tech startups. Granting equity to employees comes with some upsides:

Allows you to reduce your short term cash needs (reducing salary in place of equity)

Builds a culture of shared success and ownership

Helps to compete for top talent with the promise of a share in a potentially large outcome

Helps to drive retention (employees are less likely to leave if they are vested in the future of a company)

There are two major types of option plans with major differences in tax treatments — Incentive Stock Options (ISOs) and Non-Qualified Stock Options (NSOs). ISOs tend to be more tax advantageous and common — some of these terms will be discussed below, at a high level on the tax front:

When you exercise NSOs: the difference between the strike price of your shares and their current market value is treated as ordinary income, and you pay income tax on the gain now

When you exercise ISOs: you don’t pay standard income tax now (although the difference between the strike price of your shares and their current market value does count towards the Alternative Minimum Tax calculation which can have income tax implications for you if you qualify) and instead, you pay capital gains tax when you sell the shares (which comes with a lower tax rate if you have held the shares for longer than a year). Needless to say, if you have been granted ISOs, AMT is a critical factor in thinking through your exercise or hold strategy.

Beyond the tax implications, the other major factor for employees in deciding whether to exercise their stock options is that they need to front the cash to exercise the options (i.e. they need to pay the strike price of the options x the number of options).

For the rest of this piece, we will assume we are talking about ISO allocations (although many of the same principles apply to NSOs).

There are three key components to an ISO options allocation:

1) Vesting schedule

The most standard vesting schedules involve 4-year flatline monthly vesting (i.e. you “earn” 1/48th of your equity allocation each month) with a 1 year “cliff” (i.e. if you leave within your first 12 months you sacrifice all of your options).

Most options plans account for “accelerated vesting” in the event of a liquidity event — i.e. your options will vest over 4 years, but if we sell the company in 2 years, you will have the 4 years worth of options converted to shares pre-purchase despite the fact the last 2 years worth are yet to vest. The reason for this is that you don’t want to penalize your employees on a successful early outcome that they helped to drive toward. That said, depending on your contract, alternatives may include you carrying over your vesting schedule to the acquiring company or your sacrificing of the outstanding non-vesting options.

2) Options Value and Strike Price:

In setting the amount of options that might be suitable for a grant, the key factors will be the following:

What is the current share value? This is the current “best value” of the company (based on a recent funding round or other benchmark comps for companies at your stage and profile, etc). This is the best estimate at the present value of each share.

What is the strike price of the options? This is the “fair value” of the common shares (often set through a third party 409a valuation, which is often lower than the share price of preferred shares set by an external fundraising as those shares have preferred status which gives them a different value). This will be the price the employee must pay to exercise the options into shares. As you get later in funding rounds and closer to an IPO, the gap between the strike price of options granted to employees and the price set by 409As and funding rounds begins to narrow (options in the early stages are higher risk and therefore more likely to be worth less).

What value of options to give to the employee? The value of a single option is the difference between the strike price and the current value (so if the current value is $3 and the strike price is $0.50, each option in terms of present value is worth $2.50).

3) Rules for exercising:

The rules for an employee exercising their options can be very relevant to them. In general, employees can exercise any “vested” options whenever they want

One major area I see of difference in options plans is the rules for exercising once an employee leaves — some plans require employees to exercise vested options within 1–3 months after leaving the company or they will be forfeited (this can place more “golden handcuffs” on employees because of the tax implications mentioned previously); other plans may permit much longer timelines for employees to exercise options after they have left.

That is about as far as we will get into the structure and financial and tax implications in this piece — suffice to say, you should be aware of them.

General Rules of Thumb

Angel to Series A stage companies (1–10 FTE)

For your first key hires to the company, you will likely find it difficult to use any kind of formula for options and equity. Getting someone to join your dream before it is much of anything and has limited external validation or set equity value can be challenging, and is more of an art than a science.

The reality is that when things are so early and risky, you are not seducing someone to join your team based on the value of the equity today, but rather their share of a dream tomorrow. As a result, in the early days of a company’s development, you may need to communicate about options as a % of the total company (e.g. a senior hire might be 2–5% of outstanding equity, a junior hire might be say 0.1% or less).

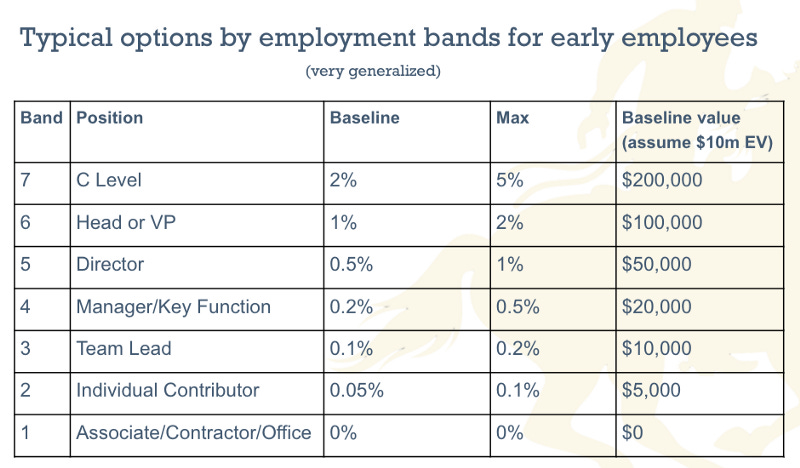

In the table below are some very general rules of thumb on typical early employee grant values as a % of the overall company’s fully diluted equity. Ultimately, the way you compensate your employees with options in the early days will vary based on how your company is performing and the status of your funding, the industry you are in, and the importance of the person/role to the company.

Some resources that might be helpful for benchmarks:

Holloway compensation guide has some good benchmarks (link)

Option Impact is a paid tool you can use to get more thorough benchmarks too (link)

Comparably has a useful calculator for looking up equity based on role and funding stage (link)

Employee roles, levels and titles at this early stage are likely more fluid and less formal than the below table might suggest.

Series B+ stage companies

Once the company has raised enough funding to signal business viability and a clearer enterprise value, and you have a bigger team (say 30+ FTE), you will likely make a shift in your options strategy and begin to communicate options not in terms of a % of the company, but rather in terms of the dollar value of the options granted (the recruitment of senior executives might still involve a discussion in terms of % of the company)

Some things that can be useful to do to determine the right dollar value of option grants to give to employees (remember that the value of the grant will be the options value less their strike price):

Develop an options grant framework that is not based on a percentage of company ownership but rather as a proportion to employee salary — the below is an example framework that might be useful for setting the options bands at each level based on average salaries at those levels

You should also think about the overall employee option pool available and how best it might be shared among the key hires you need to make

You want to finally also consider market benchmarks

E.g. if you have a VP on a $120,000 base salary, they would get 0.5x or $60,000 worth of options value. If your company is worth $20m with 10m shares outstanding and the current share price is therefore $2 per share, your VP would therefore get a 30,000 option grant ($60k / $2)

You can create brackets of equity value for each employee level — Level 6 (C Suite), Level 5 (VP), Level 4 (Director), Level 3 (Manager), Level 2 (Individual Contributor), Level 1 (Associate)

Moving up between the levels will generally take 12 to 24 months depending on performance. You may even introduce sublevels within the levels to provide employees a sense of progression

It can be helpful to set a formula for the options grant based on the salary level of the employee too.

For example, “A new Director has a salary of $100,000. They should get approximately 0.25x that in equity ($25,000). Current share price is valued at $2 so the Director should perhaps get a grant of 25,000 shares at a strike price of $1.00.”

Here’s an example of how to communicate this to an employee:

“We are granting you a salary of $100K plus 25,000 shares at a $1 strike price. The value of these options today is $2 (based on this analysis of comps and past funding valuations). The strike price is already a significant discount over the price per share paid by investors in the previous funding round. The value of these options will only grow depending on the success we as a team have in growing the organization, as we plan to do along with our investor support. For example — if we sell the company for $100M (4x current valuation), your options will be worth $100K; if we sell the company for $500m (20x current valuation), your options will be worth $500K”

Other thoughts

1) You can offer employees two compensation options

Some companies choose to offer employees two compensation options — 1) high salary and no/low options and 2) lower salary and higher options. Some companies like to do this to let the employee decide what they prefer for their own financial security needs and wellbeing. Some companies don’t like to do this as they want all employees to be more vested in growing the company or because cash is important to preserve.

2) It is best to avoid option ranges or “bands” for role levels and rather have static figures

Bands tend to have two potential flaws — 1) the person negotiating compensation on behalf of the company doesn’t understand the value of the equity and so, for ease, gravitates to the top of the band off the bat unnecessarily; or 2) the recipient finds out they’re at the low end of a band and then becomes disgruntled — you need to assume that employees will talk and will find out what each other are on. At a minimum, you will want to have the more junior roles (Levels 1–3) standardized and the senior roles can be more flexible. You want to avoid negotiating with junior new hires. Setting a fair and competitive compensation program upfront that is formulaic and standing behind it is much more advisable than opening negotiations on an individual basis. Junior roles should not get differentiated pay as a baseline — only differentiated pay based on performance in the form of a bonus.

3) Different departments may have different baselines

You might consider suggesting different % levels between departments/functions. For example — depending on the nature of the company, a VP of Marketing may be more or less valuable than a VP of Engineering.

4) Step ups between employment levels

As a general rule, you should structure each employment level to have approximately 2x the baseline grant of options to the level immediately below it. This provides some room and flexibility for you to insert more “sublevels” in between the existing levels as the company grows.

5) Create a system that revisits compensation only 1–2x a year

Do employee reviews and band resets either annually or biannually through a formalized process. Align the compensation reviews with your performance reviews.

6) It is advisable to put together an employee guide for understanding equity

The process will seem well thought out, clearer and formulaic with a guide and many employees will not understand how to value their intangible equity. It will make people more comfortable with the program. The guide should help them to be able to put an estimated value on the options grant today as well as what those shares will be worth in potentially scenario outcomes for the company.

7) There are some tools out there for benchmarks

You may want to find benchmarks for the options pool that are more specific to your geographical region and/or industry.

Good Resources

Fred Wilson’s blog post here (link) is a little outdated but a good starting point

First Round Capital has a great overview (link)

Holloway’s compensation guide has some good benchmarks (link) and Option Impact is a paid tool you can use to get more thorough benchmarks too (link)

Index Europe also has a good overview and report on options but is EU focused (link) — they suggest C Suite 0.8–1.5% (COOs can sometimes reach 2%, CTOs commonly 1%); VP 0.3–0.8% (0.2–0.7% at Series B)

AngleList has a good summary of key options terms (link)

Carta has a good explanation of the tax treatments of ISOs and NSOs under income tax, AMT, and capital gains tax scenarios (link)

For your employees, here are a few reads from Carta: